BPC-157 (Body Protection Compound-157) is a 15-amino-acid synthetic peptide gaining popularity for its supposed he

aling benefits – from repairing gut lining to accelerating muscle and tendon recovery. It’s touted in anti-aging and sports medicine circles as a “miracle” regenerative compound. However, BPC-157 is not approved for human use by any regulatory agency, and its safety remains largely unproven.

In fact, the World Anti-Doping Agency classifies BPC-157 as an S0 “Unapproved Substance,” banning its use in sports.

Amid the hype, scientists and physicians are raising red flags. Recent research suggests BPC-157 activates cellular

pathways (like the FAK–paxillin pathway) that could, in theory, promote cancer spread (metastasis). This article takes a deep dive into the science, safety data (or lack thereof), legal status, and ethical implications of using BPC-157. The goal is to provide a cautionary, evidence-based perspective for both curious patients and physicians.

Scientific Background: Healing Pathways with a Dark Side

BPC-157 was originally isolated from gastric juice and found to have remarkable healing effects in animal studies – speeding up wound healing, tendon repair, and even protecting organs from damage.

It works, at least in part, by activating the FAK–paxillin pathway in cells. FAK (focal adhesion kinase) and paxillin are proteins that regulate how cells attach and move – a crucial factor in tissue repair. For example, in tendon fibroblast cells, BPC-157 dramatically increases phosphorylation (activation) of FAK and paxillin, leading to more cell migration and survival at injury sites. This pro-migration effect underlies the peptide’s regenerative potential – essentially, it helps cells move into damaged areas and start rebuilding tissue.

The concern:the same pathways that promote healing can also be hijacked by cancer cells. FAK and paxillin are well-known players in cancer biology; aggressive tumors often use FAK signaling to invade surrounding tissue and seed metastases (secondary tumors)

By boosting FAK–paxillin activity, BPC-157 might unwittingly give any lurking cancer cells a survival or migration advantage. Similarly, BPC-157 is a potent stimulator of angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels.

Angiogenesis helps heal wounds by improving blood supply, but in cancer, new blood vessels feed tumors and facilitate their spread.

Angiogenesis helps heal wounds by improving blood supply, but in cancer, new blood vessels feed tumors and facilitate their spread.

A 2023 pharmaceutical review pointed out that BPC-157 increases expression of VEGFR2, a key receptor for vascular growth, in animal models.

The review warns that since VEGF/VEGFR2 pathways are active in roughly half of human cancers (from ovarian to melanoma).

BPC-157 could inadvertently support tumor growth and metastasis if cancer cells are present. To be clear, no study has definitively shown BPC-157 causes cancer in humans. The cancer connection is currently theoretical but plausible given these biological effects. A recent animal experiment in mice implanted with cancer cells found that adding BPC-157 did not meaningfully shrink the tumors.

While that study did not report runaway tumor growth either, the lack of a “spectacular reduction” in tumor size, suggests BPC-157 offers no anti-cancer benefit – and it leaves open the worry that it could even accelerate malignancy under the right conditions. On the other hand, a much older laboratory study (2004) reported BPC-157 inhibited growth of a melanoma cell line in a petri dish, hinting at anti-cancer effects in that very limited context.

These mixed signals underscore how little we truly know about BPC-157’s influence on cancer pathways. The bottom line is that anyone with active cancer or at risk for cancer should be extremely cautious about using a growth-promoting experimental peptide. As one set of researchers bluntly concluded: using BPC-157 “may not be the right choice, especially in situations where we are not aware of the presence of cancer cells in our body”

What Do Human Studies Say About Safety and Cancer Risk?

Despite the peptide’s popularity online, rigorous human trials are almost non-existent. To date, no clinical trial has specifically evaluated BPC-157’s potential to promote tumors or metastasis. The fears are based on mechanism and animal data, not observed human cancer cases – simply because BPC-157 hasn’t been studied in humans long enough or in enough people to see those outcomes. Here’s what we do know from the few human reports available, and why they offer limited reassurance:

- Phase I trial (unpublished): In 2015, a formal Phase I trial on 42 healthy volunteers was initiated to assess BPC-157’s safety and pharmacokinetics. However, the researchers never published the results – the trial was marked as completed, but in 2016 they “cancelled submission of the results”

This is a red flag: we don’t know if an issue or toxicity was discovered, or if it was simply a business decision. The lack of transparency means we still don’t have vetted safety data from a controlled trial.

- Small clinic case series (knee pain): One frequently cited “study” involved 12 patients with knee osteoarthritis or injury who received BPC-157 injections into the knee joint. The authors reported 11 of 12 patients improved in pain. Sounds great – until you see that it was a retrospective chart review with no control group. There was no standardized pain score or imaging to measure improvement. Essentially, the clinic administering the peptide (which the patients paid for out-of-pocket) later phoned patients to ask if they felt better, and wrote up the responses. Even the review paper summarizing this study noted the results are “not overly informative and reliable” due to the lack of objective measures. Importantly, this report was authored by physicians affiliated with a clinic selling BPC-157 injections, presenting a clear conflict of interest. This kind of self-promotional case series does not prove either efficacy or safety – if anything, it underscores the need for independent research.

- Pilot trial (bladder pain): In 2024, a private clinic published a pilot study treating 12 women with severe interstitial cystitis (bladder pain syndrome) by injecting 10 mg of BPC-157 into the bladder wall (urotoday.com). Remarkably, all 12 patients reported significant improvement in symptoms and none reported adverse effects in the short term. While this sounds encouraging, we must recognize this was not a controlled trial – there was no placebo group, and the patients (and doctors) knew they were receiving the peptide. The improvements could be due to placebo effect or the invasive procedure itself (cystoscopy), and subtle side effects might have gone unnoticed in such a small sample. Does BPC-157 cross into the body in the bladder mucosa? NOBODY KNOWS!

Moreover, this trial was conducted at a private practice and published in an alternative medicine journal, again raising concerns about bias. Like the knee report, it demonstrates that some clinicians using BPC-157 are publishing anecdotal successes, but we lack independent verification. There was also no long-term follow-up to assess if any delayed complications (for example, abnormal tissue growth or tumor formation) occurred after the injection. urotoday.com

- Older European trials: BPC-157’s discoverers in Europe have claimed success in early clinical trials for inflammatory bowel disease in the 1990s. For instance, a phase II trial in ulcerative colitis patients was mentioned in abstracts. Notably, those early reports touted BPC-157 as “free of side effects” with a “very safe profile,” even at high doses. However, these trials were never published in detail in peer-reviewed journals. The glowing safety claims – “no toxic effect… no side effect in trials”– come almost exclusively from the peptide’s original proponents. Without external oversight, such claims should be taken with skepticism. A compound affecting so many biological pathways could easily have subtler harms that small trials (or enthusiastic investigators) might miss.

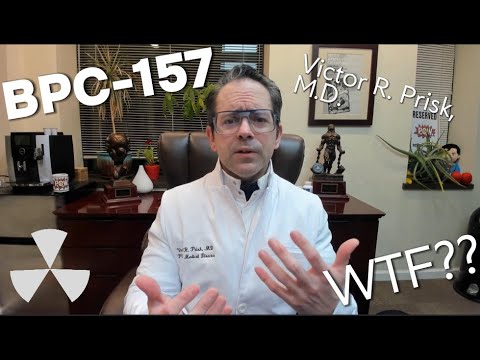

In summary, human evidence on BPC-157 is scant and of low quality. The few available human studies are small, unblinded, and often conducted by clinics with a stake in the outcome. There have been no large-scale, long-term studies to truly evaluate safety – especially not for cancer risk. As one medical commentary lamented, the literature on BPC-157 is “sparse and fraught with methodological weaknesses,” often relying on authors “who have a vested interest” in promoting the peptide. We simply do not know what happens when a person uses BPC-157 for months or years – will it cause abnormal cell growth? Will it disrupt normal immune surveillance of tumors? These questions remain unanswered. The only responsible conclusion is that oncological safety is unproven. As we at Prisk Orthopaedic & Wellness noted, without comprehensive data “we don’t know if use can cause tumors, cancer, or long-term effects on fertility”. Until real evidence says otherwise, the default assumption must be that such risks could exist.

Manufacturing and Distribution: The Wild West of Compounded Peptides

If BPC-157 isn’t an FDA-approved drug or supplement, how are people getting it? The answer: largely through compounding pharmacies and gray-market suppliers. Compounding pharmacies are specialty pharmacies that create custom formulations of drugs, typically for patients with specific needs (e.g. dye-free or liquid versions of approved drugs). In the case of BPC-157, compounders obtain the raw peptide (synthesized via solid-phase chemical synthesis) and then prepare it into injectable vials, nasal sprays, or capsules per a doctor’s “prescription.” Clinics and online “research chemical” websites also sell BPC-157 directly to consumers, often labeling it “for research use only” to skirt regulations.

For several years, this market boomed in a legal gray area. Doctors would write prescriptions to a compounding pharmacy for BPC-157 (often alongside other peptides like TB-500, CJC-1295, etc.), and patients could receive the drug despite its unapproved status. However, U.S. authorities have started to crack down:

- FDA Warning on Safety Risks: In late 2023, the FDA explicitly flagged BPC-157 as an unsafe compound to use in compounding. They added BPC-157 to Category 2 of substances “presenting significant safety risks,” noting concerns about immune reactions, peptide impurities, and lack of safety data for any human use. The FDA stated it “lacks sufficient information to know whether the drug would cause harm when administered to humans”. In plain terms, regulators are saying: we have no idea what this stuff might do to people, and we’re worried. By flagging it in Category 2, FDA signaled to pharmacies that BPC-157 is not permitted to be compounded under federal law (Section 503A) due to these safety uncertainties. Several other experimental peptides (like LL-37) were similarly banned, especially those with hints of protumorigenic effecfda.gov fda.gov co4rc.org

- DOJ Prosecution of Pharmacies: In 2020, a notable federal case targeted Tailor Made Compounding LLC, a Kentucky pharmacy that was a major supplier of peptides nationwide. Tailor Made and its owner pleaded guilty to distributing unapproved new drugs, including BPC-157, between 2018 and 2020. According to the Department of Justice, Tailor Made had to forfeit over $1.7 million in revenue from selling BPC-157 and a slew of other illicit compounds. This case was a wake-up call – it established that selling BPC-157 for human use violates the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and can lead to criminal charges. Other compounding pharmacies have since stopped openly distributing BPC-157, fearing similar action. (In clinics’ BPC-157 studies mentioned earlier, the peptide was indeed sourced from Tailor Made during that period.

FDA Warning Letters: Beyond pharmacies, the FDA has also issued warning letters to website retailers selling BPC-157. For example, in 2023 the FDA warned “Warrior Labz” (a SARMs and peptide site) that products like injectable BPC-157 are considered unapproved new drugs being sold illegally– illustrating how doctors were obtaining it before the bust.). The site had been marketing BPC-157 as a gut-healing, wound-healing therapy. The FDA’s action forced such sites to pull or hide these products. As of 2025, BPC-157 remains available mostly on the black market – through overseas companies or dubious online shops – but reputable U.S. pharmacies are generally no longer compounding it for routine use.

It’s worth noting that quality control is a serious concern for black-market BPC-157. Being unregulated, the peptide vials one buys may be of questionable purity or dosage. The FDA specifically warned about “peptide-related impurities and API characterization” problems– in other words, that what’s in the vial might not be 100% pure BPC-157, and even if it is, the peptide could degrade or contain variants. Without oversight, patients are essentially guinea pigs not just to BPC-157’s effects, but also to any contaminants. Sterility is another issue – since many take BPC-157 by injection, any contamination in the preparation could cause infections or other reactions. Indeed, one pharmacy (unrelated to BPC specifically) was hit with FDA warnings for sterility problems in its peptide injectable products.

In summary, the manufacturing and distribution of BPC-157 have been largely underground. The FDA and DOJ now treat it as an illegal drug – and for good reason, given the unknown safety profile. Patients should understand that if they are obtaining BPC-157, it is not coming from a vetted, FDA-inspected source. It’s either a compounder operating in a legal gray zone or an outright black-market supplier. This lack of quality assurance only heightens the risks associated with using BPC-157.

Ethical and Legal Implications for Doctors and Patients

The situation with BPC-157 raises difficult ethical questions in medicine. Doctors swear an oath to “first, do no harm,” and are expected to use treatments supported by evidence or, at minimum, a plausible expectation of benefit outweighing risks. With BPC-157, the benefits are unproven and the risks unknown – a scenario that challenges the ethical boundaries of clinical practice.

Is it ethical for a doctor to prescribe or administer BPC-157 to a patient? Many experts argue it is not. Unlike a sanctioned clinical trial (where experimental drugs can be used under careful monitoring and informed consent under an FDA Investigational New Drug protocol), offering BPC-157 in routine practice amounts to experimenting on the patient without oversight. As one medical ethics commentary put it, “prescribing” this compound shows an utter lack of respect for patient health and safety. The same commentary urges patients to “run from the doctors recommending this compound”, given its unapproved status.

From a legal standpoint, a physician who provides BPC-157 outside of a trial could indeed be treading into malpractice territory. Malpractice is determined by whether the physician deviated from the standard of care and caused harm. Currently, the standard of care does not include injecting or prescribing unapproved experimental peptides for injuries – there is no FDA approval or authoritative guideline endorsing BPC-157 use. If a patient were to suffer an adverse outcome potentially linked to BPC-157, the physician could be found liable for using an unauthorized treatment. In fact, some legal experts suggest that simply prescribing BPC-157 is malpractice per se, since it’s impossible to adequately inform a patient of risks that haven’t been studied. A strongly worded consumer advisory from one clinic flatly states: “The prescription of this is malpractice and you could be owed for damages.”. While that is an opinion, it reflects a growing sentiment that doctors stepping outside the bounds of evidence-based medicine with peptides are leaving themselves exposed to lawsuits.

Consider also the issue of informed consent. For a patient to truly consent to a treatment, they need to understand its risks, benefits, and alternatives. With BPC-157, no one can fully enumerate the risks – long-term safety data is absent. A doctor might inform the patient that “this peptide isn’t FDA-approved and we don’t have full safety information,” but is the patient (especially a layperson desperate for pain relief) really in a position to grasp that they are effectively a test subject? If a serious complication arose (say, an immune reaction or a cancer diagnosed down the line), the patient might argue they weren’t properly warned because the doctor themselves could not know the risks. This gray area makes patient consent legally and ethically murky. Some patients may not even realize that the peptide injection they received was investigational. Unlike enrolling in a formal clinical trial (which has extensive consent forms explaining experimental status), patients at wellness clinics might assume if a doctor offered it, it must be safe or “allowed.” Such misunderstandings could lead to feelings of betrayal and litigation if things go wrong.

Medical boards are also watching. In Australia, for example, a general practitioner was disciplined and suspended for inappropriately prescribing peptides to patients without sound justification. He admitted that giving those unapproved treatments “created a risk of harm” and that he failed to properly monitor patients. This case underscores that regulatory bodies consider it professional misconduct to experiment on patients with dubious therapies. In the U.S., state medical boards could similarly sanction physicians for gross deviations from standard care if a complaint is filed.

Can a patient sue for being given BPC-157 without explicit approval?

Potentially yes – especially if harm results. A patient who develops an illness or injury linked to the peptide could claim negligence or lack of informed consent. Even absent a clear injury, if a patient later learns their doctor subjected them to an unapproved drug without proper disclosure, they might pursue action for breach of trust or battery (unauthorized treatment). While such cases are rare (because thankfully, known serious injuries from BPC-157 have not come to light yet), the legal door is open. And if, say, a cancer patient could demonstrate that BPC-157 use accelerated their tumor (a very difficult causal link to prove scientifically, but hypothetically), the liability could be enormous.

Physicians must also consider FDA law and malpractice insurance coverage.

Prescribing an unapproved new drug outside a trial is technically illegal under the FDCA (aside from narrow compassionate-use exceptions). If a physician orders BPC-157 from a compounding pharmacy, they are arguably causing the pharmacy to violate the law (as seen in the Tailor Made case) and themselves distributing an unapproved drug. Malpractice insurers might refuse coverage if a claim arises from an activity that is unlawful or outside the scope of standard practice. This would leave the doctor personally on the hook for legal defense and damages.

Given all these factors, many in the medical community urge extreme caution. One orthopedic specialist wrote that regulatory agencies “must crack down” on practitioners and pharmacies that expose patients to unapproved peptides. The consensus among conservative, evidence-driven physicians is that BPC-157 should only be used, if at all, in controlled research settings until its safety is definitively proven. Anything less is not only risky for patients but also for the clinicians’ licenses and livelihoods.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Patient Safety and Scientific Integrity

BPC-157 exemplifies a modern dilemma: a therapy that is biologically intriguing and hyped by early research, yet lacking the rigorous scrutiny needed to ensure it’s safe for human use. On paper, BPC-157 can do amazing things – heal injuries faster, protect organs, reduce inflammation. But biology is complex; when you “turn on” growth and repair pathways, you may also be lighting a fuse for uncontrolled growth like cancer. The activation of pro-migratory signals (FAK–paxillin) and pro-angiogenic factors (VEGF, EGR-1, nitric oxide) by BPC-157is a double-edged sword. Evolutionarily, those processes help us heal and help tumors thrive. Until we know how to separate those effects, using BPC-157 in humans is a gamble with uncertain odds. From a scientific credibility standpoint, the BPC-157 story is riddled with conflicts of interest and gaps in data. Nearly all positive human “studies” have been small, uncontrolled, and authored by people selling the peptide. The lone Phase I trial’s silence is concerning. Claims that “no side effects” occur come mostly from the peptide’s inventors rather than independent investigators. Meanwhile, impartial reviews and regulatory analyses highlight what we don’t know – essentially, everything about long-term safety

Legally, the landscape around BPC-157 has shifted from quietly permissive to actively prohibitive. Federal agencies have effectively pulled BPC-157 out of legal circulation, citing the very uncertainties that should give patients and doctors pause. A doctor who ignores these signals and continues to prescribe or recommend BPC-157 is not just breaking the rules but potentially betraying patient trust.

For patients reading this: it’s understandable to be enticed by the promise of a quick fix for chronic pain or a faster injury recovery. But no reputable physician should offer you BPC-157 at this time outside of a clinical trial. If someone does, ask tough questions: Has it been proven safe? What does the FDA say? Why isn’t it approved yet? As this article has outlined, the honest answers are troubling. You have every right to be fully informed and to refuse unapproved treatments. Remember that “natural” or “not a drug” (as peptides are sometimes marketed) does not equal safe – many powerful hormones and growth factors are “natural” and can also fuel diseases like cancer if misused.

For physicians: the message is clear – patient safety and ethical practice must come before hype. Until BPC-157 is backed by solid evidence, prescribing it is a risk to your patient and to your oath. While innovation in medicine is important, it should proceed via clinical trials, not by leapfrogging around regulations and experimenting on those who trust us. There are avenues for compassionate use in truly dire cases, but a middle-aged athlete wanting to speed up tendon healing is not a case of life-threatening need. In less critical scenarios, the safest approach is to wait for data. As painful as it is to tell a patient “we don’t have a proven therapy,” it is far worse to give false hope or possibly cause harm with an unvetted substance.

In conclusion, BPC-157 remains a fascinating peptide with potential – but also a potential danger. The links to cancer-related pathways cannot be ignored, and the absence of human safety data is glaring. Both legal authorities and medical ethics counsel restraint. Until rigorous studies show that BPC-157 does not awaken any sleeping dragons (like micrometastases), it’s best viewed with deep skepticism. This cautionary stance is not anti-innovation; it’s pro-safety and pro-science. Medicine has learned hard lessons from past “cure-alls” that went awry. Let’s not add BPC-157 to that list by rushing ahead of the evidence.

IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN PROVEN BIOLOGICAL TREATMENTS FOR YOUR MUSCULOSKELETAL CONDITION, PLEASE CALL US FOR AN APPOINTMENT AT 412-525-7692

Sources:

- U.S. FDA – Compounding Risk Alert for BPC-157

- U.S. DOJ – Press Release on Tailor Made Compounding guilty plea

- Sikiric P. et al., Curr Med Chem (2012) – Early claims of BPC-157’s safety

- Jóźwiak M. et al., Pharmaceuticals (2024) – Review of BPC-157’s effects on angiogenesis and cancer concerns

- Lee E. et al., Altern Ther Health Med (2021) – Small case series on BPC-157 for knee pain (author-affiliated clinic)

- Lee E. et al., Altern Ther Health Med (2024) – Pilot study on BPC-157 for interstitial cystitis (private clinic)

- Orthopaedic & Wellness (2023) – “Peptide Dangers” blog highlighting conflicts of interest and unknown risks

- USADA – Spirit of Sport blog (2020): Warning to athletes about BPC-157’s unapproved status usada.org